How Women Developed an Exclusively Female Script in 19th Century China

How Women Developed an Exclusively Female Script in 19th Century China

Throughout history, writing has been a privilege reserved to men. There is one recorded exception: Nüshu, a writing system that was only known by women.

The story begins in Jiangyong County in Hunan province, southern China. In the 19th century, in this area women had their feet bound at the age of 7, were considered to have a duty to obey their father, husband and son and – except for a small upper-class urban minority – they didn’t have any access to education. Probably as a reaction to this male monopoly of culture, a small group of women started using Nüshu.

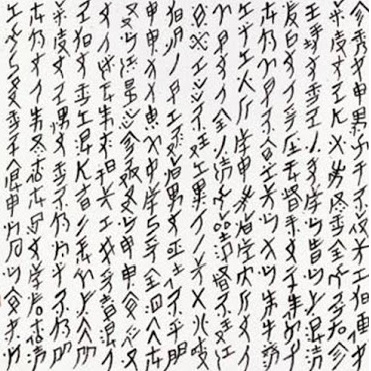

The name literally means “woman’s writing”. Nüshu (女书, in simplified Chinese) was in fact only known by women, and its practice was passed down from mother to daughter. While the history of culture could almost be reframed as a history of gendered male scripts, Nüshu is the only known case of an exclusively female one. Unlike Chinese ideograms, which are logographic, Nüshu was a syllabic alphabet; each sign stood for a sound unit in the local dialect. Around 500 texts still exist today in Nüshu, including poetries and autobiographies. Letters between “sworn sisters”, or women with a non-biological but strong bond, are also common among these documents.

Nüshu was a powerful tool of expression for women who wouldn’t otherwise have let any first-hand accounts of their lives. Today, historians use these documents to reconstruct women’s life in the past, directly from their own words.

“Its history followed the history of China”

It is not known when, precisely, Nüshu first began to be used, but the 19th century hypothesis remains prevalent [1]. However, its history certainly followed the history of China. Its use started to decline after 1949, when the rise of communism deeply transformed the structure of Chinese society and politics, including the relation between men and women. Until the 1960s, Nüshu remained almost unknown outside the province. A woman was even mistaken for a spy and arrested in the mid-60s for having a piece of paper written in this script. A few years later, as the Cultural Revolution burst, many of the texts in Nüshu were destroyed or burnt. The experts who had identified the script were sent to labour camps.

After its “rediscovery” in the 1980s, mainstream media tended to describe it as a secret script. However, field researchers have found that men were actually aware of its existence. They simply didn’t show any interest in learning it, “just as they were not storming the lofts demanding to learn embroidery”, underlines researcher Cathy Silber in an interview [2].

Although the last identified woman to know Nüshu has died in 2004, the researchers’ work has kept the script alive. A reason for that, as Silber pointed out, is that Nüshu “teaches us quite a lot about the relationship between literacy and different powered groups in society”. It is then crucial to preserve its memory.

______________________________

Join us or come take a look!

We are a group of people convinced that language skills should be more valued in the job market. For this reason we created Kolimi, a platform that connects multilingual professionals to the people and business needing them, in any field of work.

Join us to find new opportunities, or follow us on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube or LinkedIn to discover new things about languages!

______________________________

References

[2] Atlasobscura.com | “Remembering Nüshu, the 19th-Century Chinese Script Only Women Could Write”